Dark Skies, Bright Futures: Why Moths Matter in the Fight Against Light Pollution by Bee Redfield and Reed Lievers, Pollinator Partnership

Yucca moth, courtesy of Ann Cooper CC-BY-NC

Published May 30, 2025

When we think about pollinators, butterflies basking in the sunshine or honey bees humming from bloom to bloom often come to mind. But there's a hidden world of unseen, unsung, but absolutely essential pollinators working the night shift: the moths! These diverse and adaptable creatures are vitally important to plant reproduction across ecosystems.

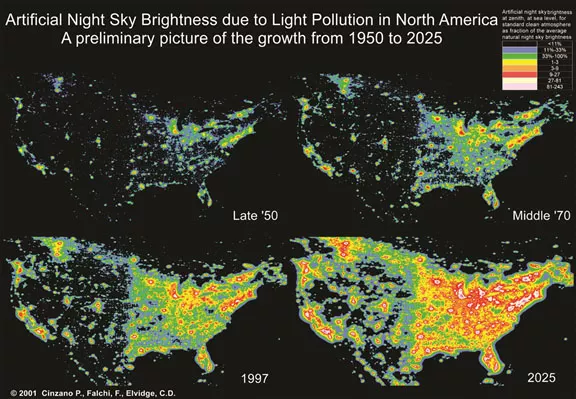

While the daytime belongs to bees and butterflies, moths take over at twilight, navigating by smells and starlight to pollinate night-blooming flowers. But as use of artificial lighting increases across the globe, that ancient nightscape is being erased, and with it, the quiet work of these nocturnal specialists.

Secret Lives of Moths

Virginia Creeper Sphinx, courtesy of Dean Smith and Indiana Nature LLC

Moths make up the majority of the order Lepidoptera, with more than 160,000 described species, vastly outnumbering butterflies (Scoble, 1995). Their ecological roles are just as expansive: from pollinating flowers to serving as food sources for birds, bats, amphibians, and mammals. Many plants are adapted specifically to moth pollination, relying on their long tongues, keen sense of smell, and unique flight patterns to transfer pollen in the dark (Macgregor et al., 2015).

Unlike bees, which typically forage within a relatively short radius of their hive or nest, moths can travel long distances, sometimes several kilometers in a single night. This makes them especially valuable in fragmented landscapes, where wild habitats are broken up by roads, agriculture, and urban development. When moths move pollen between these isolated plant populations, they help maintain variety of genetic traits within a species, also known as genetic diversity. High genetic diversity improves plant populations' resilience to disease, pests, and climate change, and supports healthy seed production. Without pollinators like moths connecting the dots between fragmented habitats, plant populations can become genetically bottlenecked, leading to reduced fertility and increased vulnerability to environmental stressors (Devoto et al., 2011).

Some species, like the famous yucca moth (Tegeticula yuccasella), even form obligate mutualisms, where both the moth and the plant depend entirely on one another for survival. These relationships are highly specialized, and disruptions like light pollution can unravel them quickly.

How Light Pollution Disrupts Moth Behavior

Artificial light at night (ALAN) disrupts moths in profound ways. Moths have evolved over millions of years to use celestial light cues from the moon and stars to orient their movement. When bright artificial light sources enter their environment, it causes a phenomenon known as “flight-to-light” behavior. Moths spiral toward the light, often until they exhaust themselves, collide with hot surfaces, or fall prey to predators (Owens et al., 2020). Light pollution can also reduce feeding by pulling moths away from nectar sources, interrupt mating by masking pheromonal signals, expose them to predators that use light as a hunting tool, and shorten moth lifespans due to stress and disorientation.

In effect, every porch light becomes a trap, undermining not just individual moths but entire ecological networks.

An Ecological Domino Effect

The decline of moths doesn’t just impact flowers, it also sends ripples through entire ecosystems. Many birds, bats, and mammals rely on moths and their larvae as key food sources. Fewer moths mean less food, fewer offspring, and more competition for scarce resources.

Worryingly, moth populations are already in steep decline. A recent review suggests global moth populations have dropped by 30–40% in just the last few decades, with light pollution, habitat loss, and pesticides all contributing to this trend.

As biodiversity drops, ecosystem resilience drops with it. Without healthy moth populations, native plant communities become more fragile and less able to resist climate stress, invasive species, and/or disease.

Lighting the Way to Solutions

Despite the grim trends, there’s a bright side: this is a solvable problem. Unlike some global environmental challenges, reducing light pollution is immediate, local, and impactful.

Municipalities like Beverly Shores, Indiana have adopted “Dark Sky” initiatives to limit outdoor lighting during key migration and breeding periods, benefiting moths and birds alike. Similar efforts are gaining traction with homeowners’ associations (HOAs), schools, and local governments, showing how individual and community action can shift policies and protect pollinators.

What You Can Do Tonight

You don’t have to overhaul your lifestyle to help. Here’s how you can reduce light pollution and support moths:

- Turn off unnecessary outdoor lights, especially during spring and summer when moths are most active.

- Use motion sensors and timers to minimize light exposure.

- Choose warm-colored bulbs (2700K or lower) over cool white LEDs.

- Install downward-facing fixtures that don’t scatter light into the sky.

- Create a moon garden with native, pale-colored, fragrant flowers that bloom at night, which are favorites of moths and other nocturnal insects. Check out our Ecoregional Planting Guides for ideas!

- Speak up at neighborhood meetings or with your HOA to promote wildlife-friendly lighting guidelines.

- Avoid pesticides and bug zappers, which indiscriminately harm beneficial insects.

- Reach out to your residential or office building manager with these suggestions.

Moths are more than fleeting shadows in the night. They are ecosystem builders, biodiversity stewards, and pollination powerhouses. As we strive to create landscapes that support life, it’s time we recognized that darkness is part of the habitat, too.

For more information about Lepidoptera conservation, visit pollinator.org/lepidoptera