Conservation Status of the Monarch Butterfly What you need to know about species protections and how you can take action

This webpage aims to help stakeholders understand the status of the monarch butterfly across North America and how to navigate the protections mandated by government regulations.

Species Protections and Regulations

United States

IN THE NEWS- December 10, 2024

The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has proposed to list the monarch butterfly as threatened with a 4(d) rule under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). A threatened species is one that is likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. While receiving the same protections as endangered species, the USFWS can issue more flexible regulations for threatened species. The ESA allows for special rules under Section 4(d) to tailor protections to the specific needs of threatened species. The 4(d) rule can modify or exempt certain prohibitions to balance conservation efforts with economic impacts, for example. This flexibility can incentivize positive proactive conservation actions. This also means public involvement can play a critical role in shaping regulatory policy that would come with a proposed rule.

Visit fws.gov/initiative/pollinators/monarchs for more information on the details of the listing decision process.

Visit the Farmers for Monarchs listing decision toolkit for information on:

Visit the Monarch Joint Venture webpage for information on:

*Please note, Pollinator Partnership does not accept public comments directly; they must be submitted to the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Visit federalregister.gov to search for a specific species, or browse the “Endangered and Threatened Species” section (federalregister.gov/endangered-threatened-species).

U.S. State Protections

In the States of California, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Texas, monarchs are covered under various state protections. These protections can result in regulations around take or possession of wildlife for scientific research, education, or propagation purposes. This applies to handling monarchs, removing them from the wild, or otherwise taking them, including captive rearing. Often, special permits are required for these types of activities. Check out your state department of fish and wildlife website for more information.

Canada

In December 2023, the Government of Canada listed the monarch as an endangered species under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). This means that on federal lands, it is illegal to kill, hurt, or catch a monarch caterpillar, egg, or chrysalis. These lands include National Parks, National Wildlife Areas, military bases, First Nation reserves, and federally owned or administered land. For more information, visit canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/factsheets/monarch-butterfly.html

Mexico

In Mexico, the monarch butterfly is considered a species under special protection and the Mexican government actively works to conserve their habitat and population. The species is legally protected within the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, which is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. For more information visit descubreanp.conanp.gob.mx/en/conanp/ANP?suri=108

How You Can Help Protect the Monarch Butterfly

Regardless of the mandated protections for the monarch butterfly in your region, conservation efforts are needed now more than ever, and everyone has a role to play in helping this iconic species thrive. Check out our Pollinator Steward Certification program to learn more about how you can help monarchs and all pollinators pollinator.org/psc

Farmers

As a farmer, you have one of the greatest opportunities to support monarch butterflies throughout their breeding and migration. However, you may wonder how these protections could affect how you manage your land. In most cases, there are regulatory certainty mechanisms that can safeguard you from being impacted by federal and state protections for the monarch. In fact, voluntarily participating in monarch conservation, by installing habitat or implementing other best management practices, can offer multiple benefits. Not only could you become eligible for various federal financial assistance programs, but you would also enjoy the positive ecosystem services provided by supporting pollinators on your land. Check out fws.gov/service/conservation-benefit-agreements for more information on how you can support the monarch while maintaining your land management flexibility.

If you are a farmer and would like to explore how to welcome monarchs and other pollinators to your land, visit pollinator.org/bff to learn more.

Gardeners

Gardeners can play an important role in establishing habitat and connectivity for monarchs along their migratory pathways. By planting native milkweed and other nectar plants, you can support monarch breeding and fuel the monarch’s journey to and from their overwintering grounds. Check out Pollinator Partnership’s plant selection resources for ideas of what to plant to support monarchs and other pollinators. Keep in mind that if you intend to tag or rear monarchs you must refer to the federal and state restrictions that may impact those activities.

If you are a gardener and want to help monarchs, check out pollinator.org/bfg to learn more.

Land Managers and Corporations

As a land manager, you and your institution can support monarchs and other pollinators on a large-scale. By incorporating pollinator best management practices into your general operations, you can often receive financial and time reduction benefits. Review your integrated pest and vegetation management plans to see if you can be doing more to promote the monarch. Consider incorporating habitat enhancements and monitoring into your plans that can support monarchs and other vital pollinators.

If you are a land manager looking to include monarch conservation in your activities, visit pollinator.org/monarch/monarch-resources#resources to learn more.

Pesticide Applicators

Pesticide applicators can follow easy best management practices when applying pesticides so that they do not inadvertently harm monarchs and other pollinators. Check out the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign’s Pesticide Education Task Force for more information: pollinator.org/nappc/pesticide-education

Educators and Researchers

The monarch butterfly and its lifecycle offer a wonderful to educate and inspire people of all ages. As educators and researchers, your expertise is critical to understanding monarchs' needs and guiding efforts toward their recovery. Keep in mind that if you intend to tag or rear monarchs you must refer to the federal and state restrictions that may impact those activities.

Check out the BeeSmart School garden kit for youth education ideas:

Check out the Lepidoptera research grants for funding opportunities: pollinator.org/lepidoptera

Check out our partners’ websites for more information:

About Monarch Butterflies

Monarch butterflies are an iconic species, easily recognized by their large and vibrant orange wings. Monarchs carry out one of the most incredible cross-continental journeys in the animal kingdom, travelling upwards of 3,000 miles from Canada and the northern United States to the oyamel fir forests in the mountains of Mexico. Unfortunately, the monarch butterfly migration is declining and work needs to be done to protect and sustain future populations.

Learn about our monarch programs across North America below!

Monarch Biology

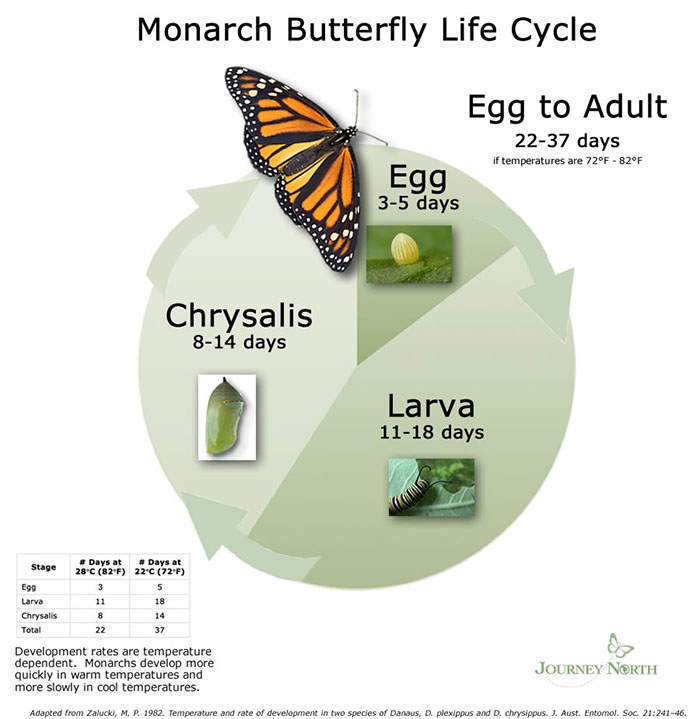

The monarch butterfly, like other insects with complete metamorphosis, has four distinct life stages: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis), and adult.

- A female monarch butterfly lays between 100 to 300 eggs during her life. The eggs hatch about four days after they are laid.

- When larvae first hatch, they are less than 1 centimeter (cm) and grow to be about 5 cm in 10-14 days. Monarchs have five instars. They molt (shed their “skin”) between each instar, to accommodate growth.

- In 8-15 days, the monarch develops from a pupa to an adult. The completion of the four life-stage process is called complete metamorphosis.

- The emergence of the butterfly (adult stage) from the pupal stage is called eclosion.

Habitat Needs

Asclepias speciosa

Milkweed

Many butterflies rely on a single plant species or multiple species in the same genus as a food source for their larval stage, with larvae typically eating plant parts (for example, leaves, flowers, buds). This type of plant is called a host plant. Milkweed is the host plant for the monarch. The larvae eat milkweed, and without milkweed, the larva would not be able to develop into a butterfly.

Monarchs use a variety of milkweed species as host plants. Milkweed contains chemical compounds called cardenolides, which are compounds that are poisonous to most vertebrates (animals with backbones) but don’t hurt the monarch caterpillar. Some milkweed species have higher levels of these toxins than others, making the monarch poisonous to potential predators.

The adult monarch and monarch larvae are both brightly colored, serving as a warning to potential predators that they are poisonous. Unsuspecting predators only need to taste a monarch butterfly or larva once to learn not to eat them again. Most animals quickly spit them out.

Nectar Plants

Adult monarchs feed on nectar from flowers, which contain sugars and other nutrients. Unlike the larvae that only eat milkweed, adult monarchs feed on nectar from a wide variety of flowers and will visit many kinds of flowers in their search for food throughout the year.

An abundance of nectar sources is especially important for migrating monarchs. Monarchs that are preparing to migrate south to Mexico need to consume enough nectar to build up fat reserves. The food they eat before and during their migration must not only power them through the long journey, but also sustain them throughout the winter. Overwintering monarchs feed very little or not at all. As monarchs travel south, they will gain weight as they continue to feed on nectar-bearing flowers.

In North America, monarchs leave the overwintering sites in the spring. Nutrition from early spring nectar bearing wildflowers provides the energy and nutrients for these monarchs to make their long journey north. When they arrive at their spring breeding grounds, they will lay eggs and then die. As the next generation of monarchs emerge, they will make their way to their summer breeding areas. It will take three more generations of monarchs to complete their journey northward and then start the cycle all over again.

Photo courtesy of Gene Nieminen, Photographer, 2013

Overwintering Habitat

Monarchs travel to overwintering sites to escape the cold climate. Overwintering habitat takes the form of forested groves, perfect for roosting. Like mammals hibernating in the winter, monarch butterflies consume enough nectar to sustain themselves throughout the winter without having to feed. However, monarchs do require water from streams, puddles, or even dew on tree leaves when overwintering.

Roosting and Refuge Sites

Monarchs are diurnal migrators, meaning they fly throughout the day and rest at roosting sites at night. From Spring through Fall, the tops of trees and shrubs make for perfect roosting sites, where large clusters of butterflies often gather. Trees and shrubs provide adequate protection from wind and help insulate butterflies from cold temperatures overnight. The importance of roosting and refuge sites for monarch butterflies necessitates their conservation and protection.

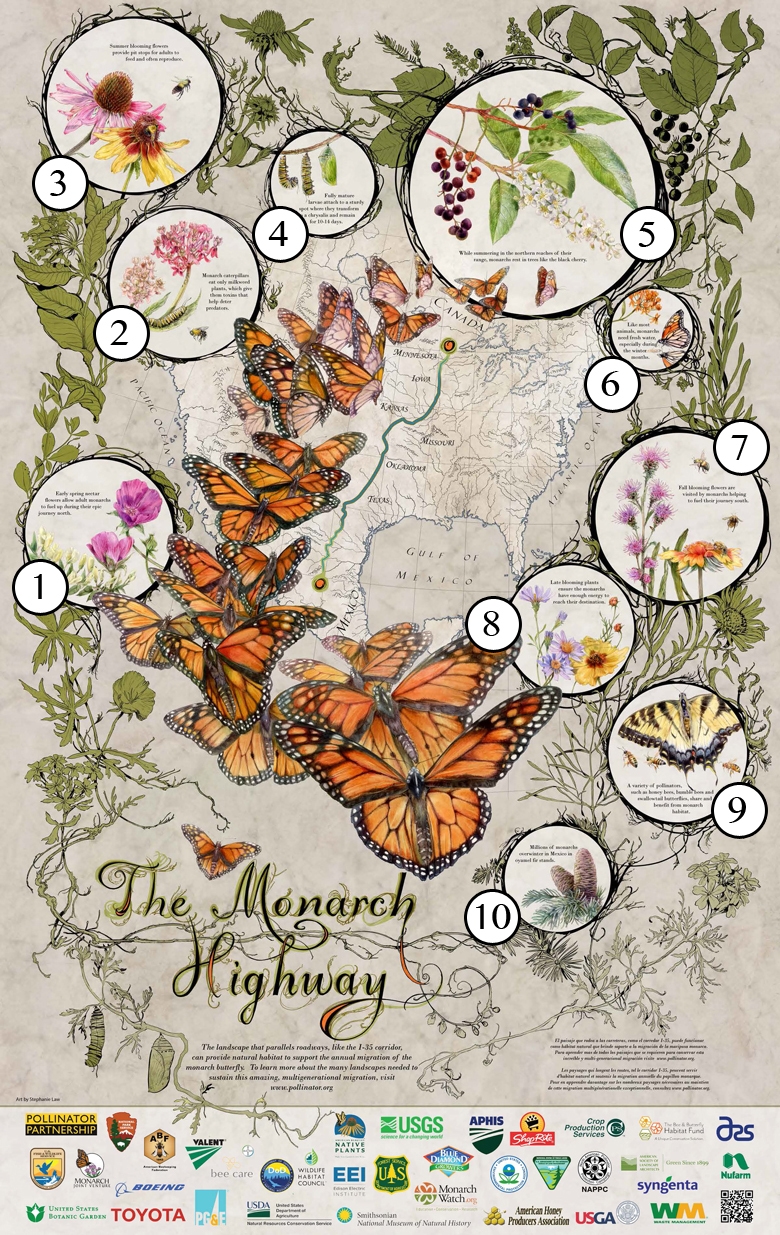

Habitat Corridors and Connectivity

Nectar corridors are a series of habitat patches along the monarch migration route that contain plants which flower at the appropriate times during the spring and fall migrations. These patches provide stopping-off points for the migrating butterflies to refuel and continue their journey. Having these islands of nectar sources is particularly important within large areas of urban and agricultural development. The patches or corridors of nectar that monarchs follow are like stepping-stones across a stream to complete their migration.

Habitat loss, often exacerbated by climate change, is the leading threat to global biodiversity loss. Migrating species are at a higher risk of extinction because they must find suitable habitat at the start and end of the migration journey and at many suitable sites for refueling and resting along the way. To combat habitat loss, wildlife corridors can be implemented to increase habitat connectivity. Wildlife corridors are strips of habitat connecting populations separated by human development such as roads or buildings. Monarch habitat corridors may consist of protected areas that contain enough nectar plants and roosting and breeding sites. Another vital characteristic of habitat corridors is the absence of unnecessary pesticide usage.

Monarch Migration and Overwintering

Monarch Butterfly Fall Migration Patterns. Base map source: USGS National Atlas.

Eastern Migration

Every fall, North American monarch butterflies make the journey from their breeding grounds to overwintering sites. Located east of the Rocky Mountains, the eastern population travels from their summer breeding grounds down to Mexico. They survive this long journey by making stops at refuge sites with abundant nectar and shelter from the harsh elements. The eastern population overwinters in the same 11 to 12 mountain areas in the Mexican States of Mexico and Michoacan from October to late March. Less than 20 overwintering sites host more than 20 million monarchs per roost.

Monarchs roost for the winter in Mexico in oyamel fir forests at an elevation of 2,400 to 3,600 meters (nearly 2 miles above sea level). The mountain hillsides of oyamel forest provide an ideal microclimate for these butterflies. Here, temperatures range from 0 to 15 degrees Celsius. If the temperature is lower, the monarchs will be forced to use their fat reserves. The humidity in the oyamel forest assures the monarchs won’t dry out, allowing them to conserve their energy.

The overwintering generation starts its journey back north in March into southern U.S. states, laying eggs in breeding grounds along the way.

Apart from loss of habitat, pesticide use, urban development, and climate change, the eastern monarch migration is also at risk due to illegal logging. While government policies promote sustainable forest management practices, unregulated (illegal) logging activities still account for forest loss in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in the Oyamel Fir Forest. Indirect impacts from illegal logging may also include increased rates of water diversions for human use, which can impair the monarch’s ability to locate proximal water resources.

Western Migration

Congregating on the branches of eucalyptus, Monterey cypress, Monterey pine, and western sycamore trees, monarch butterflies cluster in colonies to stay warm. Between February and March, the western monarch population, situated west of the Rocky Mountains, departs from their overwintering sites along the California coast. They then travel inland in search of habitat rich with milkweed to lay their eggs. Despite weighing less than one gram each, they are known to break the tree branches due to their massive abundance! Proper roosting sites are essential to the success of the western monarch migration. Fir, pine, and cedar trees are most often used for roosting because of their dense canopies. These canopies moderate the surrounding temperature and humidity, ideal for resting butterflies.

The western monarch population has been generally declining for many years, possibly due to loss of overwintering habitat. Increasing human development along the California coast is thought to be the driver of this loss. As with the eastern population, conservation of these western overwintering areas is key to the monarch’s survival.

Resident Populations

It may be surprising to learn that not all North American monarch butterflies migrate annually. Resident populations of monarchs remain in the same location for their entire life cycle. The science surrounding the existence of resident monarchs continues to evolve, but scientists do know that there are resident populations throughout North America and globally. The San Francisco Bay Area in California and South Florida are both home to resident monarchs. In the San Francisco Bay Area, there are an estimated 12,000 butterflies that remain year-round.

One proposed reason for the existence of resident monarch populations in these areas is the availability of milkweed year-round. However, milkweed that blooms throughout the whole year is often non-native (e.g., tropical milkweed), posing potential threats to monarch butterflies. Non-native milkweed may be linked to monarchs skipping their annual migration, laying their eggs in the resident location year-round. With year-round breeding, diseases and pathogens are more likely to plague butterfly species. This is why it is critical to only plant milkweed species that are native to your region. Doing so will help prevent the presence of resident populations that are more susceptible to diseases.

How Can You Help Monarchs?

The monarch migration occurs twice every year. Nectar from flowers provides the fuel monarchs need to fly. If there are not any blooming plants to collect nectar from when the monarchs stops, they will not have any energy to continue. Planting monarch flowers that bloom when they will be passing will help the monarchs reach their destination. Creating more monarch habitat will help work to reverse their decline.

Plant milkweed! Monarch caterpillars need milkweeds to grow and develop. There are more than 100 milkweed species that are native to North America, many of which are used by monarchs. To learn which species to plant in your region, and how to plant them, visit the Bring Back the Monarchs Campaign at: monarchwatch.org.

Plant butterfly nectar plants! Monarchs need nectar to provide energy as they breed, for their migratory journey, and to build reserves for the long winter. Include butterfly plants in your garden, and avoid using pesticides.

Download the FREE Monarch Plant List in PDF format

OR

Give a general monarch donation - conserve monarchs and help support them along their amazing 3,000 mile journey. Your support will help Pollinator Partnership plant and conserve monarch habitat with our work and various projects.