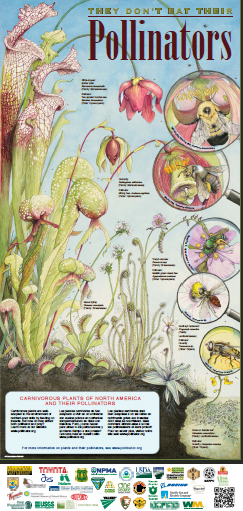

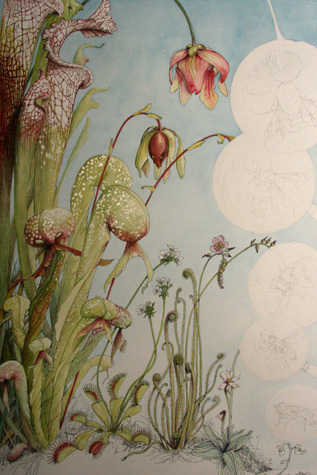

"They Don't Eat Their Pollinators - Carnivorous Plants of North America and Their Pollinators"

Carnivorous plants are well adapted to the environment of nutrient-poor soils by feeding on insects. But how do they attract both pollinator and prey?

Poster size is 37.5" H x 18" W

Click poster for larger image

About the Poster

Carnivorous plants are well adapted to the environment of nutrient-poor soils by feeding on insects. But how do they attract both pollinator and prey?

The Carnivorous Plants:

- White-topped Pitcher Plant - Sarracenia leucophylla (Sarraceniaceae)

- Cobra Lily, California Pitcher Plant - Darlingtonia californica (Sarraceniaceae)

- Tracy’s Sundew - Drosera tracyi (Droseraceae)

- Godfrey's Butterwort, Violet Butterwort - Pinguicula ionantha (Lentibulariaceae)

- Common Bladderwort - Utricularia macrorhiza (Lentibulariaceae)

- Venus Flytrap - Dionaea muscipula (Droseraceae)

Their Pollinators:

- Two-spotted Bumble Bee - Bombus bimaculatus (Hymenoptera)

- Mining Bee - Andrena nigrihirta (Hymenoptera)

- Metallic Green Sweat Bee - Agapostemon sericeus (Hymenoptera)

- Hoverfly - Toxomerus sp. (Diptera)

- Hoverfly - Helophilus intentus (Diptera)

The Carnivorous Plants

Overview

Carnivorous plants have fascinated scientists and nature enthusiasts for centuries. In 1875 Charles Darwin wrote one of the first popular books on this fascinating group of plants, Insectivorous Plants, which looked at the adaptations of these plants that allow them to live in nutrient-poor habitats. Carnivorous plants absorb nutrients from trapped insects by dissolving and digesting their prey.

While much has been studied since then on their feeding mechanisms, surprisingly few studies have examined the pollination biology of carnivorous plants. How do carnivorous plants attract both pollinator and prey? One attraction lures arthropods into a trap where the plant digests the prey, while the other attraction entices insects to carry pollen from their flowers to other plants without killing them. Natural selection has led to amazing adaptations, which have evolved independently in a number of plant lineages.

Three main mechanisms alleviate pollinator-prey overlap: spatial separation of flowers and traps, temporal separation of flowers and traps, and specific attractions to flowers and traps. Spatial separation occurs when the flowering structures are physically situated well away from the traps. Most often, the traps lie close to the ground (or underwater, as is the case of bladderworts), while the flowers bloom high atop a stalk called a scape. Temporal separation occurs when the flowers bloom at a different time before the traps develop, preventing pollinators from encountering the traps. Another mechanism occurs when flowers and traps use different attractants to lure insects: specific guidance such as UV patterns, having the traps appear unattractive to flower-visiting insects, or having the flowers appear unattractive to the prey. These attractants take the form of color, odor, or rewards (nectar, pollen, or oils).

Unfortunately, the public’s fascination with carnivorous plants has led to the poaching and over-collecting of these remarkable plants from their native habitats. Many carnivorous plants are now listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species or on government endangered species lists. Some carnivorous plant taxa are also listed by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), aimed at ensuring that the international trade of wild plants does not threaten the survival of the species in the wild. To help protect these species, please don’t pick the plants or try to transplant them. Refrain from buying specimens that may be wild-collected; only buy plants or seeds that you know were grown in a greenhouse or by cloning potted plants.

Carnivorous Plants Identification

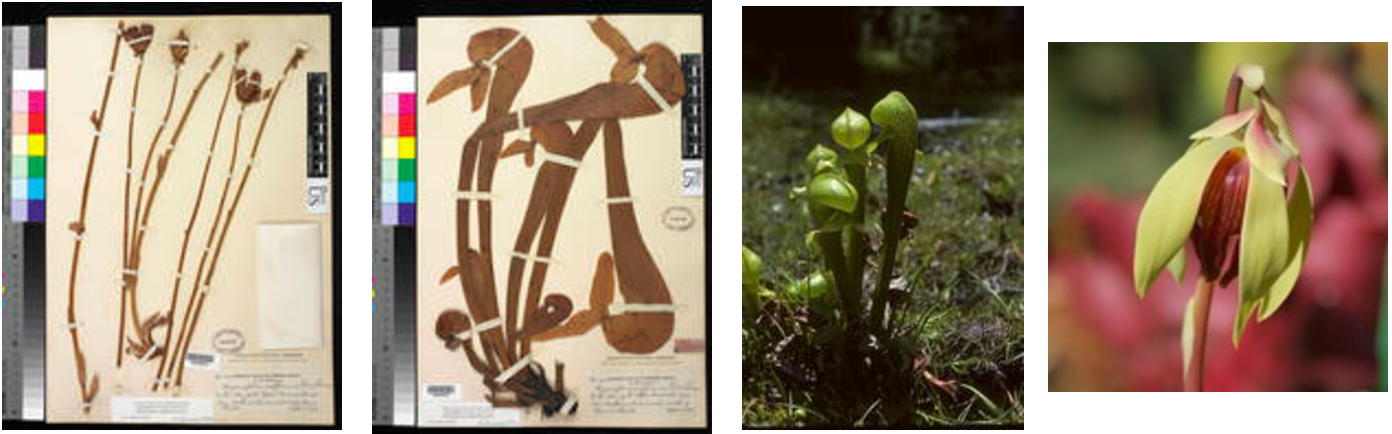

1. WHITE-TOPPED PITCHER PLANT - SARRACENIA LEUCOPHYLLA (SARRACENIACEAE)

Geographic Distribution: Southeastern Mississippi to western Florida. Once thought to be extinct in Georgia (once occurring in five counties), a privately-owned site was detected in 2001.

Pollinators: Bumble bees (Bombus), sweat bees (Augochlorella), and flies (Flecherimyia fletcheri) are known to pollinate Sarracenia species.

Habitat: Seepage areas and savanna bogs.

Size: Pitcher size is as large as 1 m, while diminutive forms (30 cm) are seldom seen. The top third of each pitcher is pigmented white.

Insect Trap: The leaves take the form of a pitcher. Insects are attracted by the color, scent, and nectar-like secretions on the lip of the pitchers. Inside the pitcher are downward pointing hairs that make retreat by captured prey challenging. The bottom of the pitcher is filled with fluid containing digestive enzymes and bacteria.

Bloom Period: Early spring before small spring pitchers, followed by non-carnivorous flat leaves in midsummer and robust pitchers in early autumn.

Flowers: Deep maroon petals.

IUCN threat status: Vulnerable (VU). Current threats include loss and degradation of wetland habitat, roadside herbicide usage, invasive exotic species (such as kudzu, Chinese privet, and Japanese honeysuckle), and collecting for horticultural trade. Listed on CITES Appendix II.

Encyclopedia of Life: Sarracenia leucophylla

Sarracenia leucophylla flowers are held singly on long stems. The structure of the flower prevents self-pollination, thus requiring pollinators to transfer pollen to other flowers. As the nectar-searching pollinator enters the flower, which hangs upside-down, the insect must pass a stigma to enter the flower chamber formed by the style. Inside the chamber, the insect comes into contact with pollen from both hanging anthers and the umbrella-like style which catches dropped pollen. When the insect exits the chamber, it must force its way under a petal, away from the stigma and preventing self-pollination of the flower. In Sarracenia, a temporal separation of flowers and traps exist, in which the flowers reward pollinators with pollen and nectar a month before the plants produce the carnivorous pitchers.

2. COBRA LILY, CALIFORNIA PITCHER PLANT - DARLINGTONIA CALIFORNICA (SARRACENIACEAE)

Geographic Distribution: Southwestern Oregon and northern California.

Pollinators: Solitary bees (Andrena nigrihirta).

Habitat: Found in sphagnum bogs, slowly draining bogs, seeps, marshy meadows, and along trickling streams.

Size: Pitcher size is often between 20 and 60 cm tall, but may vary from 1 cm to more than 1 m. The tubular leaves resemble a rearing cobra, contributing to its common name “cobra lily.”

Insect Trap: Each leaf takes the form of a “pitcher” with a hood that arches over the mouth. Insects are attracted to the color, scent, and nectar glands that cover the hood. The inner walls of the hood have short, stiff, backward-pointing hairs.

Bloom Period: Early spring before new leaves appear. From April to August depending on altitude.

Flowers: Large, showy, sweetly fragrant. Yellowish purple with five green sepals. Abundant pollen.

IUCN threat status: Lower Risk/least concern (LR/lc). Current threats include habitat destruction and collecting for horticultural trade (domestically and internationally).

Encyclopedia of Life: Darlingtonia californica

Darlingtonia californica is the only species in the genus Darlingtonia. Little is known about the pollination biology of this species. Regular floral visitors included thrips and several species of spiders, but it is unknown whether they actively carry pollen to other flowers. A published account of a generalist solitary bee, Andrena nigrihirta, which was observed visiting and pollinating D. californica flowers at five different sites in northern California (Meindl and Mesler, 2011), suggests that it is one of the most likely pollinators of this plant species.

3. TRACY'S SUNDEW - DROSERA TRACYI (DROSERACEAE)

Geographic Distribution: South-central Georgia and panhandle Florida to eastern Louisiana.

Pollinators: Sweat bees (Agapostemon), bumble bees (Bombus), syrphid flies, and meloid beetles.

Habitat: Wet sand, pond margins in pinelands, exposed lake bottoms, and raised bogs.

Size: Leaf length is 25 - 50 cm. Scapes grow to 25 - 60 cm tall.

Insect Trap: The erect, tall, filiform leaves are covered in sticky glandular hairs. The hairs produce digestive juices that decompose trapped prey.

Bloom Period: April through June.

Flowers: Pink to light purple, rarely white.

IUCN threat status: Not yet assessed. NatureServe assesses this species as G3 Vulnerable.

Encyclopedia of Life: Drosera tracyi

Sundews are found on every continent except Antarctica. Often considered a variety of Drosera filiformis, this species is the only Drosera endemic to the USA. Several species of Drosera are self-compatible and/or are able to self-pollinate and self-fertilize autonomously. It is hypothesized that the flowers on long peduncles evolved not to separate the traps and flowers but to project their flowers well above ground level to attract flying insects that serve as pollinators.

4. GODFREY'S BUTTERWORT, VIOLET BUTTERWORT - PINGUICULA IONANTHA (LENTIBULARIACEAE)

Geographic Distribution: Central panhandle region of Florida, with most sites having very few individuals.

Pollinators: Possibly bees and flies

Habitat: Open, acidic soils of seepage bogs on gentle slopes, deep quagmire bogs, ditches, and depressions in grassy pine flatwoods and grassy savannas, often occurring in shallow standing water.

Size: Rosettes are about 15 cm across. Scapes grow to 10 - 15 cm tall.

Insect Trap: The leaves are coated with glandular hairs that secret sticky mucilage. Insects become trapped when they mistake the sticky mucilage for water or nectar. The edge of the leaf slowly rolls over the insect while it is digested.

Bloom Period: February through April

Flowers: Corollas are pale violet to white, with a deep violet throat and dark veins.

IUCN threat status: Not yet assessed. Listed as Threatened by the US Endangered Species Act. NatureServe assesses this species as G2 Imperiled. The species' habitat is declining in extent and quality due to logging, shading by planted pines, and drainage alteration.

Encyclopedia of Life: Pinguicula ionantha

Of the roughly 80 currently known species of Pinguicula, just about 50% are found in Central America. A strong spatial separation of flowers and traps exist in butterworts. The flowering stalks extend high above the sticky rosette of fungal-scented leaves. A wide range of insects have been seen visiting the flowers of Pinguicula species, including beeflies (Bombylius), bees (Andrena, Anthophora, Bombus, Halictus, Lasioglossum, Osmia), hawkmoths, butterflies, calliphorid flies, small beetles and thrips. The literature is lacking in pollination biology studies of Pinguicula ionantha, a threatened species restricted to a small area in northwestern Florida. An online photograph shows a flower visited by a species of hoverfly in the genus Toxomerus.

5. COMMON BLADDERWORT - UTRICULARIA MACRORHIZA (LENTIBULARIACEAE)

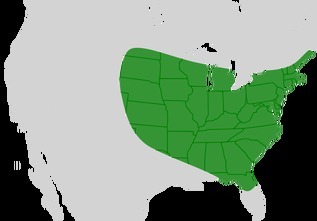

Geographic Distribution: Throughout Canada and the continental United States. In Mexico, found in Baja California and Coahuila.

Pollinators: Possibly bees and flies

Habitat: Shallow waters of lakes, ponds, bogs, marshes, and fens

Size: Flowers bloom atop a 5 - 25 cm scape

Insect Trap: Underwater bladders have a small opening sealed by a hinged door with trigger hairs. When aquatic invertebrates touch the hairs, the door releases a suction pulling the invertebrate into the bladder, where enzymes digest the victim.

Bloom Period: June through August

Flowers: Yellow, sometimes pink or purple

IUCN threat status: Not yet assessed. NatureServe assesses this species as G5 Secure.

Encyclopedia of Life: Utricularia macrorhiza

Utricularia is the largest genus of carnivorous plants, with more than 220 species, occurring on all continents except for Antarctica. It is free-floating and lacks roots. Bladderworts exhibit perfect spatial separation of flowers and traps, as the flowers bloom well above the water while the traps grow underwater. Even though Utricularia macrorhiza is far-ranging, the literature is lacking in pollination biology studies and reports of pollinator observations. An online photograph shows flower visitations by Helophilus intentus.

6. VENUS FLYTRAP - DIONAEA MUSCIPULA (DROSERACEAE)

Geographic Distribution: North Carolina and South Carolina

Pollinators: Possibly small flies and beetles

Habitat: Depressions in wet pine flatwoods and wet pine savannas

Size: The flower stalk reaches up to 30 cm

Insect Trap: The leaf blades terminate in bivalve traps with sharply toothed edges. Green on the outside, red pigment shades the insides of the trap where trigger hairs, when touched, cause the leaf to snap shut trapping its prey.

Bloom Period: May through June

Flowers: Small white flowers with faint green veins

IUCN threat status: Vulnerable (VU). The species has a requirement for frequent natural fires and an open understory. Habitat alteration and fire suppression are the largest threats. Listed on CITES Appendix II.

Encyclopedia of Life: Dionaea muscipula

Even though the Venus flytrap is perhaps the best-known carnivorous plant species, very little has been published about pollination of this species in the wild. There is a clear spatial separation of the flower atop tall scapes and the traps. The diet of Dionaea is limited to crawling arthropods such as ants, spiders, and beetles, while a very small percentage of its diet is flying insects. Though the plant is self-compatible, a 1958 report suggests that pollination is carried out by “various beetles, small flies and possibly spiders.” NatureServe reports that a rare critically imperiled moth, the Venus Flytrap Cutworm Hemipachnobia subporphyrea, specializes as a herbivore on the plant. More research on the pollination biology of this remarkable species is clearly needed.

The Pollinators

Overview

Pollination occurs when pollen is moved within flowers or carried from flower to flower by wind, water, or pollinating animals. Almost 90% of all flowering plants rely on animal pollinators for fertilization, and about 200,000 species of animals act as pollinators. Of those, 1,000 are hummingbirds, bats, and small mammals such as mice. The rest are insects like beetles, flies, bees, ants, wasps, butterflies, and moths. Plants can also be pollinated by wind and water. The transfer of pollen in and between flowers of the same species leads to fertilization, and successful seed and fruit production for plants. Pollination ensures that a plant will produce full-bodied fruit and a full set of viable seeds.

Worldwide, approximately 1,000 plants grown for food, beverages, fibers, spices, and medicines need to be pollinated by animals in order to produce the goods on which we depend. In the United States, pollination by honeybees and other insects produces $40 billion worth of products annually.

Learn more about the pollinator lifecycle here and how you can help protect them here!

Pollinator Identification

1. TWO-SPOTTED BUMBLE BEE - BOMBUS BIMACULATUS (HYMENOPTERA)

Geographic Distribution: Eastern North America, Ontario to Florida and as far west as Mississippi.

Habitat: Meadows or gardens with a diversity of flowers.

Size: Medium-sized bumble bee. Queen: length 17 - 22 mm, abdomen 8.5 - 10 mm wide. Worker: length 11 - 16 mm abdomen 5 - 6.5 mm. Male: length 13 - 14.5 mm, abdomen 6 - 6.5 mm wide.

Identification: Thorax predominantly yellow, with a dark spot in the middle, abdomen yellow at the top segment, black below.

Pollinates: White-topped Pitcher Plant - Sarracenia leucophylla (Sarraceniaceae)

Other Plants Commonly Visited: Thistles, vetches, roses, golden rod, mints

Encyclopedia of Life: Bombus bimaculatus

A widely-distributed species in the eastern United States, this bee has a medium-long tongue and visits a wide range of flowers for nectar and pollen. They typically nest below ground and not normally in the wet areas where many carnivorous plants are found, but they are strong flyers and may forage up to two miles away from their nest. This species name refers to the two distinctive yellow markings on the abdomen.

2. MINING BEE - ANDRENA NIGRIHIRTA (HYMENOPTERA)(SARRACENIACEAE)

Geographic Distribution: Northern U.S. and Canada

Habitat: Nests on thinly grassed slopes of ground. Nests are tunnels in the ground 8 - 12 in. long with side branches off the main tunnel.

Size: Females: length 10 mm; males resemble females but are slightly smaller.

Identification: Black with sparse gray hairs, especially on abdomen, some black hairs on face of male.

Pollinates: Cobra Lily, California Pitcher Plant - Darlingtonia californica (Sarraceniaceae)

Other Plants Commonly Visited: Willow, buffalo berry, wild plum, strawberry and pasque flowers

Encyclopedia of Life: Andrena nigrihirta

This is an early spring species of bee occurring late April to early May and as a result is an important pollinator of fruit bearing plants. This species has short, triangular tongues about one-third the length of long-tongued bees of a similar size. The forewings are long and pointed towards the top. Pollen is collected on the hind legs but largely near the body with large collections on the rear thorax and base of legs. They have been referred to as “sand bees” but can be found in more dense clay and silt soil. This genera as a whole is difficult to find and identify due to their grassy nest locations and the slight differences among the many species.

3. METALLIC GREEN SWEAT BEE - AGAPOSTEMON SERICEUS (HYMENOPTERA)

Geographic Distribution: Eastern North America, Manitoba to Florida and as far west as Nebraska.

Habitat: Ground nesting in soil burrows or sometimes rotting wood

Size: Length 12 mm

Identification: Metallic green head and thorax. Females have a metallic green abdomen with white hair bands in-between segments. Males have black and yellow abdominal bands.

Pollinates: Tracy’s Sundew - Drosera tracyi (Droseraceae)

Other Plants Commonly Visited: Generalist species often seen visiting asters, roses, peas, and heathers

Encyclopedia of Life: Agapostemon sericeus

This species is a solitary bee with a single adult bee per nest. Agapostemon species are differentiated from other metallic green bees by the hind tibia being equal to or exceeding the tarsi in length. There are about 40 species in this genus. Agapostemon are commonly called “sweat bees” but unlike the related Halictus and Lasioglossum genera, they are not attracted to human sweat.

4. HOVERFLY - TOXOMERUS SP. (DIPTERA)

Geographic Distribution: The genus is found in North, Central, and South America

Habitat: Meadows or gardens with flowering plants

Size: Medium-sized fly

Identification: A combination of black and yellow stripes, only one set of wings, and large compound eyes that nearly cover the head. Males can be distinguished from females with their eyes meeting at the top of the head.

Pollinates: Godfrey's Butterwort, Violet Butterwort - Pinguicula ionantha (Lentibulariaceae)

Other Plants Commonly Visited: Species in this genus visit flowers of a large number of plant families.

Encyclopedia of Life: Toxomerus

Toxomerus is a large genus with many species, distributed throughout the New World. The color patterns typically mimic wasps, which provide them some protection from predators. They are active and agile flyers, and can hover (hence the common name) in place for extended periods. They don’t have long tongues so can only collect nectar from relatively shallow flowers, but they will also visit flowers to eat pollen. Hover flies mimic bees and wasps.

5. HOVERFLY - HELOPHILUS INTENTUS (DIPTERA)

Geographic Distribution: United States and Canada

Habitat: Meadows or gardens with flowering plants

Size: Medium-sized fly

Identification: Black horizontal stripes on the abdomen on a yellow background, and vertical stripes on the thorax.

Pollinates: Common Bladderwort - Utricularia macrorhiza (Lentibulariaceae)

Other Plants Commonly Visited: Some Asteraceae (sunflower family)

Encyclopedia of Life: Helophilus intentus

This species, as is true for many in the family Syrphidae, is considered a mimic of the warning color pattern of yellow and black found on wasps such as yellow jackets. They are active and agile flyers, and can hover (hence the common name) in place for extended periods. They are common flower visitors, collecting nectar and eating pollen, but not much is known in detail about their importance as pollinators or even the diversity of flowers they visit.

Credits

This webpage was made possible with the help and advice of many people. We especially want to thank the following people for their much appreciated input!

Dr. Stephen Buchmann received his doctorate in entomology from the University of California, Davis. His current research interests include native bee nesting behavior, conservation biology and pollination ecology, especially buzz pollination.

Joe Engler is a US Fish and Wildlife Service Regional Wildlife Biologist for the National Wildlife Refuge System in the Pacific Northwest. His duties include Regional Pollinator Conservation Coordinator and Regional Monarch Conservation Coordinator.

Dr. David Inouye is a Professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Maryland, College Park. David is on the Steering Committee of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, on the Board of Directors of the National Phenology Network, and the Scientific Advisory Board of the Endangered Species Coalition.

Gary Krupnick is the head of the Plant Conservation Unit in the Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. His research examines how data from herbarium specimens can be used in assessing the conservation status of plant species.

The Artist

Teri Nye is a self-taught artist, illustrator and photographer specializing in recording nature. She holds a Bachelor of Science in biology/botany, a Master of Landscape Architecture and a teaching certification in biology. She has been drawing and photographing plants and animals her entire life and is currently a member of the Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance, the Georgia Botanical Society, and the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators. When not drawing, photographing or enjoying nature, she teaches workshops on drawing and plants and works as a graphic designer for the Atlanta Botanical Garden. Her portfolio is available at terinye.com

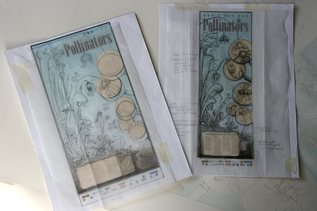

The Poster Design Process

The design started with small sketches on tracing paper over a basic layout created in a digital layout application. Working at a small scale made it easier to scan sketches and experiment with scale and layout.

Once the design was approved, each of the possible pairings between plants and pollinators began. Information was gathered by talking to experts, reading scientific papers and collecting photographs of the plants and pollinators in their natural habitats. The science team checked each pair.

Detailed sketches of each species and flower were made before adding these to the composite sketch.

For the general poster layout, rough sketches were scanned and placed in a digital file then printed at full size as a guide. Another tracing paper overlay was made to add more detail to the drawings.

Once the drawing was completely planned it was transferred to watercolor paper. All the preliminary drawing on tracing paper minimized erasing on the watercolor paper. Finally the drawing was painted in watercolor. The final painting was professionally scanned and added as a layer in the digital document.

Tools and Materials

Graphite pencil, tracing paper, light table, Arches 260 lb. hot press watercolor paper, watercolor (Schmincke, Winsor & Newton, M. Graham & Co.), layout: Adobe InDesign

Photos

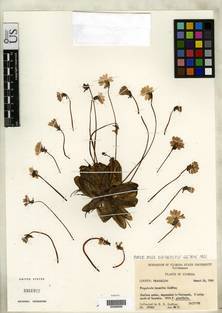

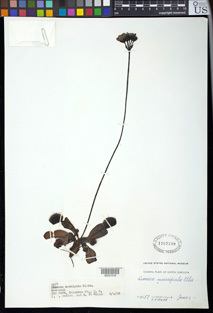

All plant specimen images courtesy of the U.S. National Herbarium, Smithsonian Institution: Department of Botany Collections

Joe Engler – Sarracenia leucophylla, Darlingtonia californica

Theodore F Niehaus – Darlingtonia californica

J.D. Ripley – Dionaea muscipula

G.A. Cooper - Sarracenia leucophylla

Richard Bartz - Wikimedia Commons: Helophilus intentus

Tim Ross - Wikimedia Commons: Drosera Filiformis Tracyi

Vivian Negron-Ortiz - Wikimedia Commons: Pinguicula ionantha

Noah Elhardt - Wikimedia Commons: Utricularia macrorhiza

Gilles Gonthier - Wikimedia Commons: Toxomerus marginatus

The Packer Lab - York University

Ron Hemberger - Bug Guide

Web Resources

Botanical Society of America: Carnivorous Plants

Bug Guide

International Carnivorous Plant Society

North American Insects and Spiders: Syrphid Fly – Toxomerus marginatus

Discover Life

Encyclopedia of Life

IUCN Red List

Plants Across Melbourne Blog: The Definitive Guide to Carnivorous Plants

Text Resources

Anderson, B. and J.J. Midgley. 2001. Food or sex; pollinator-prey conflict in carnivorous plants. Ecology Letters 4: 511-513.

Ceska, J. 2001. Leucos lost and found. Georgia Botanical Society, BotSoc News 75(7): 1-2. D'Amato, P. 2013. The Savage Garden, Revised: Cultivating Carnivorous Plants. Ten Speed press. 384.

Jürgens, A, A. Sciligo, T. Witt, A.M. El-Sayed, and D.M. Suckling. 2012. Pollinator-prey conflict in carnivorous plants. Biological Reviews 87(3): 602-615.

Meindl, G.A. and M.R. Mesler. 2011. Pollination biology of Darlingtonia californica (Sarraceniaceae), the California Pitcher Plant. Madroño 58(1): 22-31.

Roberts, P.R. and H.J. Oosting. 1958. Responses of Venus fly trap (Dionaea muscipula) to factors involved in its endemism. Ecological Monographs 28: 193-218.

Wilson P. 1995. Variation in the intensity of pollination in Drosera tracyi: selection is strongest when resources are intermediate. Evolutionary Ecology 9: 382-396.

Mitchell, T.B. 1962 Bees of the Eastern United States. North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin No. 152.

Schnell, D. 2009. Carnivorous Plants of the United States and Canada. Timber Press. 468.

Sponsors

Thank you to all the "Carnivorous Plants of North America and Their Pollinators" Poster Sponsors